By Paul Evans

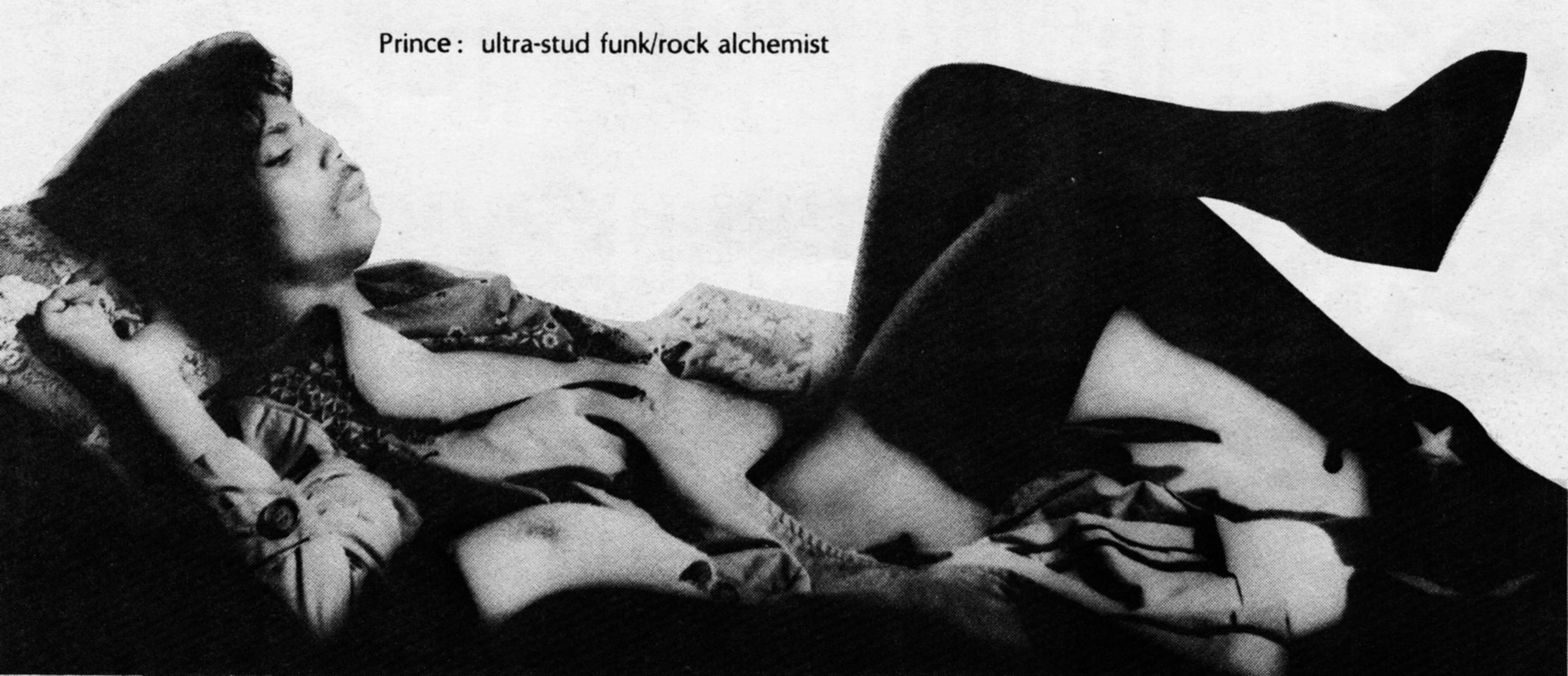

Blessed with both the ultra-stud distance and star quality of Jimi Hendrix and the fey elegance of pre-born again Little Richard (rock's original Little Queenie), Prince is one of the more compelling funk/rock alchemists on the scene today. Hailing from unlikely Minneapolis (not the Duckhuntersville some people assume but by no means Funkytown), he's given us a third album, Dirty Mind, that further develops an important new synthesis -the bass drum thump, treble guitar infectiousness of black funk crossed with Chuck Berry rock and roll that also incorporates the melodic synthesizer work of techno New Wavers like the Brains and Gary Numan.

This is underlined by a visual presentation equally amalgamated -a near Dreadlock hairstyle, a rocker's uniform recalling the Rocky Horror Picture Show or glitter boys like Marc Bolan of T. Rex, and a Rude Boy button that acknowledges both the Ska bunch (Madness, Specials, etc.) and, indirectly, the Clash. He has a cherub's voice like Smokey Robinson but sings about incest, oral eroticism -the whole "life between the sheets" subject matter as if the source of his inspiration was the Penthouse Forum. Plainly then, Prince, a black pioneer, though definitely chic is not Chic or the Commodores or the Gap Band. With little of their slickness and a lot of their catchiness, he can also rock and roll.

When Prince and his tough band performed at the Agora a while back, not only were black women swooning as they might for Teddy Pendergrass and black men dressed like the boys in G.Q. nodding cool approval, but rockers were there too, and for once this usually musically segregated city became something like the words to his song "Uptown": "Black, White, Puerto Rican/Everybody is a-freakin' ".

Prince is but one bright light in a most interesting aspect of recent pop music: its rediscovery and reliance on rhythm - music's first ingredient that, more than melody, moves and inspires us.

When Queen, after their first validity as Mott the Hoople-esque rockers, piled excess upon excess with glitzy production, artsy/inane lyrics, vocals like a bad dream of a barbershop quartet overdubbed to 64 tracks, finally scored their mega-hit, it was with "Another One Bites the Dust" that, while far from profound, moved mightily across the airwaves in clean, repetitive, undeniable funk onslaught. Blondie, always more popsters than punkers, followed their disco smash "Heart of Glass" with this year's model of The Funk, "Rapture"- a white rap that, though it doesn't match the goofy cleverness of Grand Master Flash or the Funky Four + One or even Kurtis Blow, combines the nursery rhyme talkiness and bangbang rhythm of the more charming of the rap records. Meanwhile, out on the left coast, it's not only the smokey fervor of Michael McDonald's R & B inflected voice that has resurrected the Doobie Brothers, but the artful syncopation that is L.A.'s equivalent of The Funk (on such hits as "What a Fool Believes") that transformed this band from a tired FM rock cliché to a sprightly rhythmic force.

The New Wave has not been unaffected by the new rhythm awareness. ·Where the Clash's first two albums effectively relied upon a militant 4/4 as a metronomic metaphor for their soldierly pursuit of new values, London Calling gave us a band that had discovered swing and shifting rhythm with the kind of joy Michael Philip Jagger must've felt when he first turned on the radio and heard James Brown. Drummer Topper Headon and bassist Paul Simonon solidified their mastery of the reggae beat, thus musically underscoring their allegiance to Jamaica and its apocalyptic poor boy's vision of a new and fairer world. With Sandinista!, their three LP set drawing on reggae and its sophisticated partner, dub, as well as Motown bass riffs, gospel's thumping sonority, and once again, white rock and roll's drive; this brave band has created a music large enough to underlie its lyrical concerns - third world solidarity and a tough compassion held out toward all those moving to a different drum.

The New Wave has not been unaffected by the new rhythm awareness. ·Where the Clash's first two albums effectively relied upon a militant 4/4 as a metronomic metaphor for their soldierly pursuit of new values, London Calling gave us a band that had discovered swing and shifting rhythm with the kind of joy Michael Philip Jagger must've felt when he first turned on the radio and heard James Brown. Drummer Topper Headon and bassist Paul Simonon solidified their mastery of the reggae beat, thus musically underscoring their allegiance to Jamaica and its apocalyptic poor boy's vision of a new and fairer world. With Sandinista!, their three LP set drawing on reggae and its sophisticated partner, dub, as well as Motown bass riffs, gospel's thumping sonority, and once again, white rock and roll's drive; this brave band has created a music large enough to underlie its lyrical concerns - third world solidarity and a tough compassion held out toward all those moving to a different drum.

Biracial English bands like the aforementioned Madness, Specials, and the Selecter derive their power from ska, reggae's precursor that pounds with the same jagged uplift. Earlier this year, the Police found ready audiences in such out-of-the-way places as North Africa and the Mideast for their music that sounds like reggae on a big budget, somewhat popified but still propulsive.

In a more studied manner, David Byrne and Brian Eno traveled to Ghana for a firsthand look at The Funk. Their collaborations with African players, musicians from Parliament and Labelle can be heard on Talking Heads' Remain in Light and Byrne/Eno's My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (well-reviewed in MUZIK!, Vol. 2). They combine the near monotone chord structures and rhythmic complexity reminiscent of Miles Davis' On the Corner with freeform lyrics or taped segments of Moslem chanters or gospel groups to create a blend of sophistication and passion that embraces both Western and Eastern worlds of fervor.

All this follows an honored tradition. Elvis' early fire was lit by Arthur Crudup and the blues, the Stones dug Otis and Jimmy Reed, the Beatles were inspired by Motown's more melodic but nonetheless beat-crazy sound. David Bowie, the artist of the 70s/'80s most willing to take chances, realized the power of the disco rhythm that at that time was shunned by most rockers. That the more astute of today's white players draw verve from reggae, ska, African, third world and funk sources is no surprise. But what is this monster Funk and how did it come about? In the early '60s, cycloning out of Augusta, James Brown begat a music that increasingly had little to do with verse/verse/chorus/verse standard song form. Instead, like chant and African percussive music, it downplayed melody and chordal variation in favor of a steady bass and drums mix hooked on a simple musical phrase repeated to the point of trance and fever. The words were often inspired meaninglessness - a point expressed simply by J.B. himself, "It's a new day, so let a man come in and do the Popcorn!" - but that was all right , because when Brown popped corn, it was the backbeat that counted.

Some of his players and some of his spirit continued in the music of "The Riot Master", Sly Stone. Generally less raw, easier than James Brown, he appealed to both blacks and whites: "It's a family affair." But whereas Sly saw things in familial terms, that just didn't seem quite big enough for the next man in line...

Funk as religion, Funk as Way of Life came fully into play with the elevation of George Clinton as High Priest. Along with fellow Funkateer Bootsy Collins, Clinton's near interchangeable bands, Parliament and Funkadelic created a musical world based on The Funk, The Whole Funk and nothing but The Funk. Dressed in outfits that would have shamed the Temptations on even the drunkest of a Halloweens, they raised a joyful noise that elevated the bass guitar to a divinity’s status, threw in out of joint synthesizers and space age bleeping (come down from Jazz Funkter Sun Ra), and made up a language punch drunk with puns and mega-jive. "Tear the roof off the mother sucker!" became the battle cry with Parliament/Funkadelic, Bootsy's Rubber Band, Parlet, The Brides of Funkenstein and other Funkarnations of Clinton's irretrievably funked up mind fighting dullness, slickness, and pretentiousness all symbolized by arch enemy, Sir Nose D'Voidoffunk.

So, fear not George, and the rest of you huddled, dancing masses. Disco's demise, no surprise. Cowboy wear, really square. But The Funk lives on, and will continue to do so because it's as close to us as a heartbeat. And with Prince, Rick James and the Bus Boys trying out rock and roll, and white musicians of all ·persuasions incorporating more challenging rhythms, pop music has nothing but good to gain from this cross-fertilization.